Singapore General Hospital will NEVER ask you to transfer money over a call. If in doubt, call the 24/7 ScamShield helpline at 1799, or visit the ScamShield website at www.scamshield.gov.sg.

We’d love to hear from you! Rate the SGH website and share your feedback so we can enhance your online experience and serve you better. Click here to rate us

What happens when we start to question the stories we carry about our worth?

In my years as an art therapist in an adult acute hospital here in Singapore, I've met patients from all walks of life. Each has a story, unique and complex. But some just… stay with you. This is one of them.

The referral read simply:

“Male, 60s. Stroke. Post-stroke depression. Family conflict. Lives in nursing home. Poor coping.”

That's it. Just one stark paragraph, lost in a system of thousands.

But in art therapy, we don't just stop at the referral.

We sit. We listen. We wait.

For the first few sessions, this patient would ask if I could help him with transport or waive his bills. Gently, I’d redirect him back to our medical social work team. Again. And again.

Then, one day, the question changed.

He asked, quietly, almost like a whisper: “You want to know who I used to be?”

He was the youngest son, “the runt of the litter,” he told me with a slight, wry half-smile.

He grew up stealing eggs, scrambling up rambutan trees, sometimes getting chased by neighbours wielding wooden sticks.

His mother worked multiple jobs to make ends meet. His father wasn't around.

He grew up fast.

“Men last time, we just tahan,” he said, using that familiar Malay word we understand in Singapore, meaning to endure. “Cannot cry. Cannot fall sick. Cannot be tired.”

He became a father of three. He worked hard, always.

His pride? That he never, ever showed weakness.

Until the stroke.

And suddenly, the man who never rested… couldn’t move. Couldn’t speak clearly. Couldn’t even feed himself.

In art therapy, we spend a lot of time listening for what isn't said. Sometimes, the deepest grief isn't expressed in words—but in what the body can no longer do. It's in the quiet, the stillness.

There’s a powerful idea I often reflect on, sometimes attributed to Carl Jung: “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” (This powerful distlilation of Jung's thought is often associated with concepts found in his Collected Works, particularly around Aion, 1951).

A stroke may physically interrupt blood flow in the brain, yes. But the rupture it causes in one's very identity?

That goes far deeper, straight to the core of who we believe we are.

It was in our seventh session when he finally picked up a pencil. For the very first time.

He’d made many excuses before. “Hand not strong,” he’d grumble. “I cannot already,” or simply, “No point lah.”

But my art therapist gut sensed that it wasn’t truly about ability.

It was about fear.

Fear of what might emerge on the page. Fear of years of unspoken emotion, stored up, finally seeing the light. Fear of facing a self he simply didn’t recognise anymore.

He drew a circle.

And then another.

And another.

When I asked gently what the circles felt like, he said, his voice quiet:

“Like being trapped.”

A few sessions later, the circles morphed. They became ceiling fans.

That’s what he saw every single day—lying in his bed at the nursing home.

The fan. Always spinning. Never stopping. Never actually going anywhere.

The shaking blades, the monotonous sound it made, the fixedness of it all.

It haunted him.

It was more than just a fan. It was the chilling metaphor for the prison of his new life.

Motion without movement.

Noise without direction. A relentless, pointless whirl.

And then one day, a single tear appeared.

Not a loud sob. Not a dramatic cry.

Just a quiet, solitary drop, slipping out at the corner of his eye.

It's a sacred thing, that first tear. It’s like the soul saying, “I’m letting you in.” It wasn't dramatic, no. But it was profoundly, deeply human.

It made me think of my own father, and the fathers I know.

How much pain do our men carry in silence? Where does it go, when they’re told to "be strong" and "just tahan" their entire lives?

Does it settle in the chest? The gut? The jaw?

Does it harden? Does it fester?

Then came the writing.

In art therapy, we don't direct, don't instruct: “draw this” or “write that.”

We simply meet people where they are, with whatever they bring. And that day, he just picked up the pencil and started to write.

The words came out in clear, deliberate penmanship, a stark confession:

我是废物。

“I am useless.”

I didn’t interrupt. I didn’t offer comfort.

Sometimes, the best thing a therapist can do… is to simply not speak. To hold the space.

He wrote about his family. About deep shame. About feeling like an utter failure. About how no one needed him now.

About how he couldn’t even wipe himself clean.

He just kept writing. It was like watching a man finally speak to himself for the first time in years.

We talk about the triangular relationship in art therapy—between the client, the therapist, and the art itself.

And in moments like this, I don't look at the client directly.

Not out of avoidance, never. But out of a profound sense of respect.

To hold that vulnerable space without crowding it.

When he ran out of space on the paper, his gaze returned to that first, searing line.

我是废物

And then, with a slow, deliberate movement, he added one small, powerful mark.

我是废物?

“Am I useless?”

That tiny question mark changed everything.

He wasn’t declaring it anymore. He wasn’t stating a fixed truth. He began asking. He started searching.

That subtle, monumental shift—from a definitive statement to an open question—is everything. It’s where the light gets in.

Some frameworks, like CBT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy), help us challenge thoughts directly, bringing them into the rational light.

But in psychodynamic and Jungian thought, change often happens deeper, in the symbolic, unconscious realm.

Where truths surface slowly, in their own time.

And healing begins not from pure logic, but from a profound connection to meaning.

That day, something truly shifted within him. The spinning fan in his mind… it seemed to pause.

The fixed, trapping circle… gently became a question, an opening. A crack had appeared. And through it, light began to stream in.

I share this not because it’s rare or extraordinary. But because it’s incredibly common—just often missed.

We meet patients who are labelled as “refusing treatment,” who “aren’t motivated,” who “don’t engage.”

But what if their struggle isn't about mere compliance—but about a deep-seated question of their own worth?

What if their anger masks an ocean of grief?

What if their resistance… is, in fact, their very last, precious form of dignity?

This is where the arts and humanities don’t just matter. They are essential.

They don’t just help us treat.

They help us see. Truly see.

If you’re a healthcare worker reading this—how might this shift change your next patient encounter?

If you’re a caregiver for a loved one—what old, quiet stories might they be carrying, beneath the surface?

And if you’ve ever felt like your worth is only as good as what you can do—maybe this is a story for you too.

Because sometimes, the beginning of healing…

is simply a single question mark.

Disclaimer: The patient described in this essay is a fictional composite of several individuals I worked with as an art therapist.

Phylaine Toh is a Faculty Member at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Medical Humanities Institute and Manager at the SGH Office of Well-being. With over 7 years of experience in trauma-informed care and arts-based clinical practice, she now focuses on weaving narrative and humanistic approaches into clinician wellbeing and healthcare education.

This story was first posted in HEART. Scan the QR code to join and read more stories

We love mail! Drop us a note at lighternotes@sgh.com.sg to tell us what you like or didn't like about this story, and what you would like to see more of in LighterNotes.

Contributed by

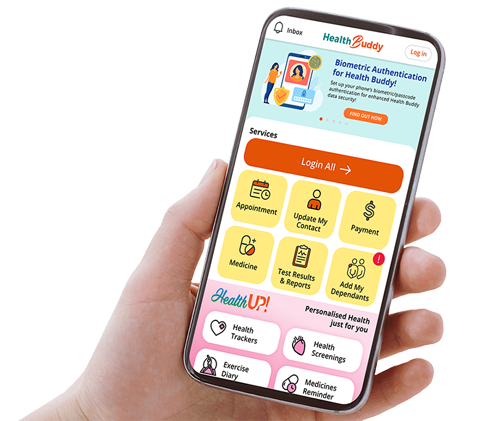

Stay Healthy With

Outram Road, Singapore 169608

© 2025 SingHealth Group. All Rights Reserved.